We navigate the world both physically and mentally.

This ability largely hinges on what scientists call the “cognitive map” – an internal representation of the world that helps us understand and interact with our surroundings.

Despite its crucial role in daily life, the cognitive map is not a perfect reflection of reality.

Instead, it is a constructed internal “virtual reality” model that can be distorted by various factors.

This article delves into the reasons why our cognitive map diverges from reality, exploring the:

- Psychological

- Neurological

- And cultural influences

that shape our perception.

The Nature of Cognitive Maps

A cognitive map is essentially a mental representation of the layout of reality.

It helps us:

- Navigate the world

- Remember things

- And plan our lives.

The concept was first introduced by psychologist Edward Tolman in the 1940s, who suggested that rats create mental maps of mazes to navigate them more efficiently.

This idea has since been extended to people, who use cognitive maps for a range of spatial and abstract tasks.

However, cognitive maps are not photographic reproductions of our world.

They are subjective and constructed, influenced by our:

- Experiences

- Emotions

- And cognitive processes.

Even though they aren’t real, they are what give us our perceived options in life.

And these choices become our reality.

Here are several factors that contribute to the discrepancies between our cognitive maps and actual reality:

Perceptual Limitations

Our senses are the primary gateways to forming cognitive maps, yet they are inherently limited and prone to errors.

Visual perception, for example, can be influenced by factors such as:

- Lighting

- Perspective

- And motion.

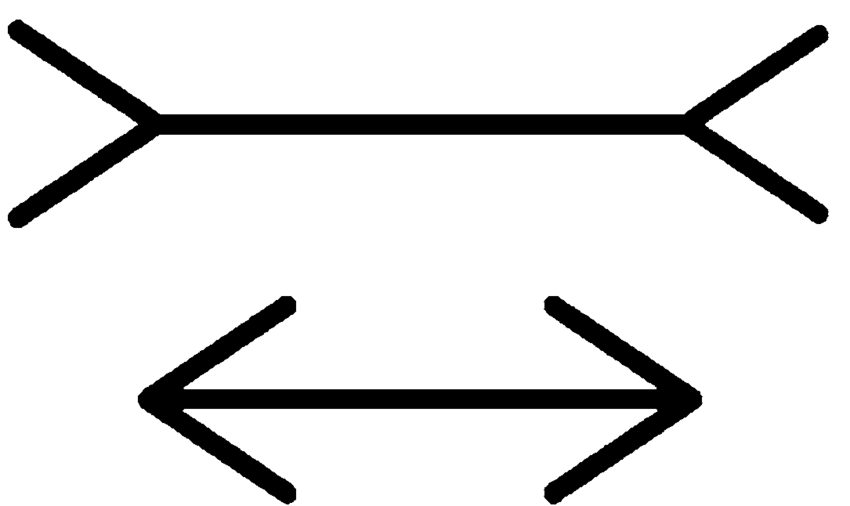

Optical illusions vividly illustrate how easily our visual system can be tricked.

For instance, the Müller-Lyer illusion, where lines of equal length appear different due to the orientation of arrowheads, demonstrates how context can distort perception.

Similarly, auditory perception can be deceived by phenomena like the McGurk effect, where conflicting visual and auditory signals result in altered auditory perception.

These sensory limitations mean that the raw data we receive from the environment is already a skewed version of reality.

Cognitive Biases and Heuristics

The human brain is wired to use shortcuts, known as heuristics, to process information quickly.

While these shortcuts are often useful, they can also lead to systematic errors known as cognitive biases.

One such bias is the anchoring effect, where people rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the “anchor”) when making decisions.

This can distort our cognitive maps by causing us to overemphasize certain features of our environment while neglecting others.

Another relevant bias is the egocentric bias, where people perceive and remember events in a way that centers around themselves.

This can lead to distorted spatial representations, as people might overestimate the importance or prominence of locations that are personally significant.

Neurological Constraints

Neurological factors also play a significant role in shaping cognitive maps.

The brain structures involved in spatial navigation, such as the hippocampus, are crucial for forming and maintaining cognitive maps.

Damage to these areas, as seen in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, can severely impair spatial navigation and memory.

Moreover, the brain’s plasticity means that cognitive maps are constantly being updated and reshaped based on new:

- Experiences

- Habits

- And information.

This dynamic nature can lead to inconsistencies and distortions, particularly when new information conflicts with existing knowledge.

Social and Cultural Influences

Our cognitive maps are also influenced by the social and cultural contexts in which we live.

Different cultures emphasize different aspects of the environment, which can shape how people perceive and navigate reality.

For example, indigenous Australian cultures have been shown to use cardinal directions:

- North

- South

- East

- West

as primary references in their cognitive maps, rather than egocentric directions:

- Left

- Right

- Front

- Back

commonly used in Western cultures.

Language plays a crucial role in this process.

Linguistic relativity, the idea that the language we speak influences the way we think, suggests that people who speak different languages have different cognitive maps.

For instance, speakers of languages with numerous terms for specific spatial relations might develop more detailed and nuanced spatial representations.

Emotional and Psychological Factors

Emotions and psychological states can significantly distort cognitive maps.

Anxiety, for instance, can cause people to perceive distances as longer and obstacles as more daunting than they actually are.

This phenomenon is known as “affective realism,” where our emotional state colors our perception of reality.

Similarly, past experiences, particularly painful ones, can alter cognitive maps.

Someone who has been mugged in a specific location might perceive that area as more dangerous and avoid it, regardless of its actual safety.

Implications and Applications

Understanding that our cognitive maps are not perfect representations of reality has important implications.

In fields like urban planning and architecture, acknowledging the subjective nature of spatial perception can lead to designs that better accommodate human navigational tendencies and preferences.

In the realm of psychology and business, recognizing the impact of cognitive biases and emotional states on perception can inform strategies.

For example, exposure therapy for anxiety disorders often involves confronting distorted cognitive maps and gradually reshaping them to align more closely with reality.

Your success depends on building more accurate and flexible cognitive maps.

If you aren’t getting results in some area, it’s because your cognitive map is not enriched enough.

Conclusion

Cognitive maps are fascinating and complex models that highlight the interplay between perception, cognition, and reality.

While it enables us to navigate the world effectively, it is not a flawless mirror of our environment.

- Perceptual limitations

- Cognitive biases

- Neurological constraints

- And social and emotional factors

all contribute to the distortions in our cognitive maps.

By recognizing and studying these distortions, we can develop strategies to alter their effects and enhance our understanding of the world.

Ultimately, embracing the imperfect nature of our cognitive maps can lead to a deeper appreciation of the human mind’s remarkable ability to navigate the complexities of both physical and mental landscapes.

Want to learn how to build better cognitive maps?

Read “Timeline Meditations“.

It’s a collection of golden maxims designed to help you grow.

Enjoy.

-M.I.

You May Also Like:

Mental Models - How To Discover The Fortune Hidden In Your Own Mind

How to Gain Unshakable Conviction in Contrarian Plays

REVEALED: The Easy Way To Quit Any Bad Habit

Unlock the Genius Secrets of Leonardo da Vinci: 8 Hacks To Boost Creativity

A Guide to Smarter Decision-Making: Understanding and Applying Positive Expected Value (EV+) Moves

Top Tech Billionaire Warns: If You Wait for 100% Certainty, You’ve Already Lost the Game (Do This In...

WARNING: 11 Traits That Make You Allergic To Money (Signs You Won't Be Rich)

Why 99% of Advice Is Toxic - and How to Identify the 1% That Will Change Your Life Forever

My name is Mister Infinite. I've written 600+ articles for people who want more out of life. Within this website you will find the motivation and action steps to live a better lifestyle.